Author: Bibby, Claire1

Published in National Security Journal, 05 April 2021

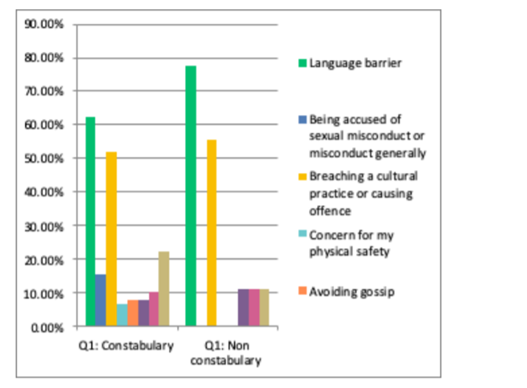

The data was then considered in relation to whether the person was a constable or non-constabulary. Most of the constabulary staff (62.34%) and non-constabulary staff (77.78%) identify language barriers as the main issue preventing communication with people of a different gender. Breaching a cultural barrier or causing offence is a similar barrier for constables (51.95%) and non-constabulary staff (55.56%). However, only constables (15.58%) identify that being accused of sexual misconduct or misconduct generally is a communication barrier and that this is likely to hinder or deter them from communicating with people of a different gender. Additionally, more constables (22.08%), compared to non-constabulary staff (11.11%), are concerned about protecting the NZ Police reputation and said this is a barrier to communicating with people of a different gender. The constables’ concerns may be an outcome of the Bazley report on police conduct which resulted in ten years of Government monitoring of police performance to develop an ethical workforce with standards, policies and guidelines to prevent inappropriate or unprofessional sexual behaviour.23 By not talking to people of a different gender for fear of sexual or other misconduct allegations, the constable potentially keeps their personal reputation and the reputation of police, safe.

Figure 10: Constabulary and non-constabulary responses to the question “Thinking about your international policing experience, what is most likely to hinder or deter you from communicating with people of a different gender to you. Select any that apply.”