Author: McCarthy, Loren1

Published in National Security Journal, 03 November 2024

Download full PDF version – Seeing the Futures: Evaluating the Application of Structured Analytic Technique Alternative Futures Analysis (613 KB)

Abstract

The Structured Analytic Technique (SAT) Alternative Futures Analysis (AFA) is an imaginative thinking technique used by intelligence analysts in circumstances of uncertainty to generate and explore a range of potential future states. Recent literature on SATs has been critical of their use because of an absence of robust evidence of their value. This research observed focus groups which applied AFA to a specific case study and evaluated their outputs. The results suggest AFA can be used less prescriptively than some of the literature sets out in terms of group size and timeframe, while also supporting the recommended use of a facilitator. An understanding of the purpose of AFA as an imaginative thinking technique, intended to explore future possibilities, is vital in applying the technique, evaluating it, and communicating the results. The potential for mismatch between the criteria suggested to analyse SATs in general and the intent of AFA as a technique, undervalues the technique. A key consideration in evaluating AFA, is the need to ensure the technique is applied as intended. Further, this research identifies that the learning context may influence the application of AFA.

Keywords: Structured Analytic Technique, Alternative Futures Analysis, Intelligence Analysis, Futures Studies, Scenario Generation

Introduction

Structured Analytic Techniques (SATs) are the name for a group of methods intended to improve intelligence analysis with the intent of allowing transparency, externalising thought processes, and mitigating bias. Efforts to improve analytic processes are not new; the need for ‘alternative analysis’, to challenge the user to consider alternatives, was identified in the 1980s. The terror attacks of 11 September 2001 and the intelligence controversy concerning weapons of mass destruction in Iraq of 2002 are considered to have intensified wider efforts to improve analysis. Some of the initial shortfalls identified in these cases were ‘failure of imagination’, failure to challenge key assumptions, and to consider alternatives. Following these cases, the scope of alternative analysis was expanded to structured analysis.

SATs are intended to provide transparency, instill rigour, and address subjectivity introduced into analytic processes through bias. They are often supported by specific guidance for analysts to follow. The intent is that by following a structured and transparent process, the probability of error introduced by bias is reduced. SATs are also intended to facilitate transparency through illustrating the process behind judgments. They can be used as structured processes to enable collaboration on problems. Grouped by purpose, SATs include diagnostic techniques, which illustrate arguments, assumptions or gaps, contrarian techniques, which challenge thinking, and imaginative thinking techniques, which seek to develop different perspectives or outcomes.

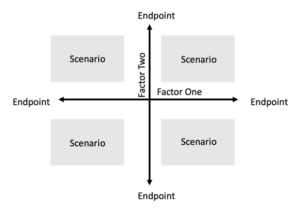

Alternative Futures Analysis (AFA) is an imaginative thinking or scenario technique used in complex situations when the future outcome may be uncertain. AFA requires the user to select the two most uncertain and critical factors in relation to a particular issue, and consider how the interaction of these two factors might shape the future. These factors are somewhat inconsistently referred to as factors, forces, drivers, or uncertainties throughout the literature. Factors are intended to represent ‘driving forces’ which are considered likely to influence the future. Joseph Nye suggests that estimators should not attempt to predict the future, but should aim to present alternative futures, and the signposts which might identify alternative paths. In this sense, AFA is not intended to predict what the future will be, but instead to imagine a range of scenarios that explore what the future could be. Following this, each scenario can be mapped back to the present, and indicators can be developed which might be used to track whether a particular future may be developing. The technique is believed to have been developed by military planners, but is also used in business. The work of Herman Kahn and the RAND Corporation in the 1950’s in scenario planning is considered to have paved the way for the consideration of hypothetical futures. The most well-known use is the frequently cited 1970s use of the technique by the Royal Dutch/Shell corporation to prepare for future oil crises.

The method of AFA is described across literature, as applied across a wide range of disciplines. In the policy realm the UK Government Office for Science’s 2017 “The Futures Toolkit” refers to it as ‘Axes of Uncertainty’. Randolph Pherson also presented a variation of AFA called Multiple Scenarios Generation, which essentially uses a similar method to AFA, but facilitates the use of more than two factors.

The method of AFA, as presented in United States Government’s “A Tradecraft Primer: Structured Analytic Techniques for Improving Intelligence Analysis”, is summarised as follows:

- Develop the issue being considered

- Brainstorm relevant factors that affect the issue

- Select the two most critical and uncertain factors to turn into axes

- Establish relevant endpoints

- Create a matrix from the two selected axes

- In the resulting matrix (Figure 1), develop stories describing the futures created by the combination of the two factors. Develop indicators for these futures.

The value of AFA is in its ability to manage and explore uncertainty. It is considered a divergent thinking technique that describes multiple outcomes for consideration, rather than predicting a single outcome.1 AFA assists consideration of otherwise surprising developments, and allows for the development of indicators to monitor signs that an identified future possibility might be likely to occur.2 The value is ultimately the ability to consider how decisions or policy may perform in each of the futures, and develop agile or flexible approaches.3

The term ‘alternative futures’ is also used in the literature in a general sense to describe the idea that ‘the future is plural’.4 There are multiple methods of developing alternative futures.5 Underpinning AFA is the concept that in theory multiple possible futures exist.6 Thus the idea of alternative futures shapes the understanding of the specific method of AFA through facilitating the exploration of multiple futures beyond that considered most likely.

The limitations of AFA are not particularly clear in the methods. The resources required to facilitate AFA can be significant, with multiple sources suggesting it is labour intensive, requiring considerable time in hours or days, and the involvement of experts in addition to numbers of analysts.7 The primer also refers to being open to engaging in the process, which is described as more ‘free-wheeling’.8 Pherson is perhaps most prescriptive in presenting the methodology, stating AFA should only be used for ‘simple situations’, over a longer time frame (three to 10 years).9 The participation of 24-40 participants is recommended, with facilitation by a team (of four).10 Pherson categorically states the technique should not be used if there are more than two critical factors.11 Ian Wing specifically outlines problems to look out for when using AFA.12 These include scenarios which could be ambiguous, and that unexpected developments could influence all of the futures. Wing also suggests that the concept of extrapolating trends itself relies overly on historic examples, meaning ‘wild cards’ (defined in the context of futures studies by Elina Hiltunen as ‘rapid (and in that sense surprising) events that have vast consequences…’)13 may be discounted. Wing however appears confident that all of these potential weaknesses can be addressed.14

_______________

1 Loren McCarthy holds a Master of International Security (intelligence) from the Centre for Defence and Security Studies, Massey University. This article is based on her research dissertation. The author would like to acknowledge the contribution of Dr John Battersby, Senior Fellow at Massey University’s Centre for Defence and Security Studies, as supervisor of this research project. Dr Battersby’s guidance, expertise, and support has been invaluable. Any correspondence in relation to this article, please contact the Managing Editor, NSJ at CDSS@Massey.ac.nz.